Posted December 15, 20147:19 am

The Legal Aid Society of Cleveland was featured by NBC News today. The focus was the important work Legal Aid does to ensure healthy communities. Click here to read more - or browse the full story by Seth Freed Wessler and Kat Aaron below:

CLEVELAND, Ohio—When Tony Cox, 53, woke up in the hospital after suffering a heart attack when he fell off a ladder during a roofing job, he figured he'd hit bottom. "All I could think about was getting better and getting back to my family," he says.

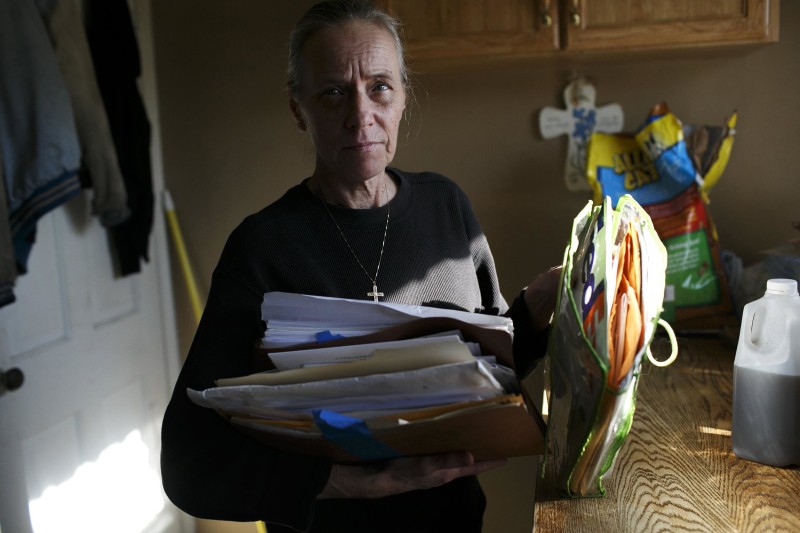

But that day in the hospital was not his lowest point. Over a year later, a sheriff's deputy arrived at the modest two-bedroom house Cox shares with his wife Donna and their now 16-year-old son bearing a notice that their home was in foreclosure. Out of work from the injury, Cox had fallen behind on mortgage payments. "We were getting ready to be homeless, to move in with family," Donna says. "We would have been separated."

MADDIE MCGARVEY / FOR NBC NEWS

MADDIE MCGARVEY / FOR NBC NEWS"When we really look at the issues in our clients' lives," says Colleen Cotter, the director of Legal Aid Society of Cleveland, "there's almost always a health issue involved. Poverty is unhealthy, and bad health can lead to economic chaos. I see everything we do as increasing the health and communities we serve."

The Legal Aid Society of Cleveland started their partnership in 2003 as a joint effort with the Metro Health System, which operates the city's safety net hospitals and clinics. Called the Community Advocacy Program, it was one of the country's first medical-legal partnerships with on-site hospital and clinic-based attorneys to provide direct legal support to patients.

The program, which in 2015 will expand from three to four attorneys stationed in hospitals and clinics, served over 1,000 patients this year. Just over half of these patients were children and their families, referred to legal services by pediatrics departments.

"In general, medicine does not spend much time on the parts of patients' lives that we can't fix," he said.

On a recent afternoon, Needleman sat at a row of computers with a group of new medical residents showing them how to use a database that sends legal-issue referrals directly to the legal services attorney whose office is on the hospital campus.

He implores the students to make a practice of asking patients and their parents about issues that may not be immediately about health. According to Cleveland Legal Services, the most common referrals are for education law issues, followed by immigration law, family law and health-care related cases.

"The attorneys can get in and advocate for the families we see in ways we just don't have the knowledge or time to do," Needleman said. "The challenge is getting the medical community to pay attention to these kinds of issues enough to make the referrals."

Healthcare providers say that expanded access to insurance through the Affordable Care Act is a major step toward closing the link between poverty and illness. But even good healthcare can't address the rest of a patient's life.

"If you ask them directly if they have a legal need, yes or no, people will say no," says Megan Sandel, medical director of the National Center for Medical Legal Partnerships, a group founded in 2006 that supports programs like the Community Advocacy Project across the country. "But if you start digging down into specific issues—housing, utility shut offs, domestic violence—they will open up."

MADDIE MCGARVEY / FOR NBC NEWS

MADDIE MCGARVEY / FOR NBC NEWSWhen Sandel was seeing patients at the Boston Medical Center, she treated a homeless family whose child had developmental delays. The mother wanted a specialized educational plan for her child, but had no success navigating the school system. The clinic's on-site lawyer got the crucial educational plan. A year later, Sandel's phone rang. The mother was calling to see the lawyer. The son was doing well, but a hard-won housing voucher was about to be lost, because her apartment hadn't passed inspection and she couldn't find a new one in time.

"I was able to literally walk up a flight of stairs" to the lawyer and get a letter seeking an extension on the housing search, Sandel says. "Within 15 minutes we were able to solve this problem."

Putting lawyers on site means a "very limited resource" - free legal aid - is "in a place where families are going to go." And for doctors, the partnerships let them do what they do best, Sandel says. "Having a lawyer as part of their health team lets them go back to being doctors."

For families, it's the personal savings that matter. In Cleveland, Maria Guerrero, 34, whose whole family receives care from a Metro Health affiliated medical clinic, the lawyers at the doctor's offices have come to her defense twice, most recently in 2013 when an attorney at her health clinic helped stave off homelessness, which often leads to poor health.

That year, Guerrero was up against a financial wall. Two years earlier, her husband was deported to Mexico for a driving violation. Without his income, Guerrero, who was born in Chicago and has lived in Cleveland since the mid-90s, was struggling to pay rent in the apartment she shared with a friend. She was banking on the arrival of more than $8,000 in Earned Income Tax Credit, a tax return for low-income families.

But in March, the tax preparer she had used for several years told her someone had already used her Social Security number to file a tax return. She'd been the victim of identity theft, and the IRS would need that cleared before a check could be mailed.

Guerrero, who was pregnant at the time, reported the theft to the IRS and filed a police report. But no check arrived. Finally, she learned the check had been mailed to an incorrect address. In August, with no check, Guerrero gave birth to her daughter through cesarean section, and was forced to go on maternity leave from her job as a machine operator at USA Cotton.

She fell behind on rent and her roommate told her she would need to leave.

"I was really getting ready to be homeless with my kids," she said.

MADDIE MCGARVEY / FOR NBC NEWS

MADDIE MCGARVEY / FOR NBC NEWSIn October, Guerrero brought her baby to a checkup at the McCafferty Health Center, a small community clinic that's part of the Metro Health system. Veronica Crowe-Carpenter, the pediatric nurse practitioner that Guerrero's kids had seen for several years, asked her about any stressors in her life. And immediately, Guerrero began to tell of her pending eviction and the lost check.

Crowe-Carpenter sent Guerrero down the hall to speak with Megan Sprecher, the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland attorney with an office in the clinic. Sprecher listened to Guerrero's case and looked into the details. "It was a very simple issue," Sprecher says, "but these systems can be hard to navigate if you're not familiar with them."

It turned out that the EITC check had been mailed first to Guerrero's old address and then send to the address associated with the person who'd stolen Guerrero's identity.

"Being in the clinic," Sprecher says, "makes legal assistance accessible and people trust us. This is the place they come for medical care, and our work is an extension of that."

"If that check had not come, we would have been in a shelter," Guerrero says.

From Crowe-Carpenter's point of view, the partnership helps her do her job. "Medical education is not set up to focus on the social aspect of people's lives," Crowe-Carpenter said. "I understand that health is social and exists in a larger context, but we are often unable to do anything about that context. That's where Megan fits in."